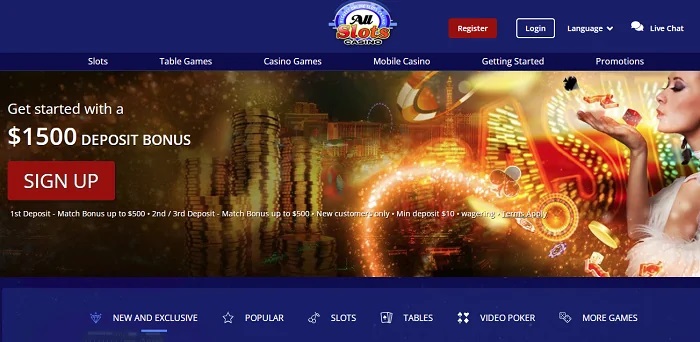

All Slots Casino – Free Spins, Real Money Games, and More

All Slots Casino stands as a beacon in the online gaming world, offering an immersive experience that combines the thrill of Las Vegas with the convenience of home gaming. Imagine a portal where every spin on the slot machine, every deal of the cards, and every roll of the dice brings the exciting atmosphere of a real casino to your screen.

- Diverse Experience: Whether you’re a casual gamer or a high roller, the variety at All Slots Casino is unmatched.

- Accessibility: Experience the ease of gaming on any device, a testament to the inclusive nature of All Slots Online Casino Australia.

- Welcome Offers: New players are welcomed with open arms and enticing All Slots Casino free spins and no deposit bonuses, ensuring everyone gets a flying start.

- Continued Excitement: Not just stopping at the welcome, the casino keeps the excitement alive with more All Slots Casino free spins no deposit opportunities as you continue playing.

- Real Money Gaming: There’s a thrilling edge to playing with All Slots Casino real money, elevating the gaming experience to new heights.

- Safe and Secure: When you engage in All Slots Casino real money games, rest assured of a secure environment that values your privacy and security.

At All Slots Casino, it’s not just about the games. It’s about the joy, the community, and the endless possibilities that come with each click. Here, every moment is an opportunity to experience something new, exciting, and uniquely yours. Welcome to a world where gaming comes alive. Welcome to All Slots Casino.

The Allure of All Slots Casino

Immerse yourself in the captivating world of All Slots Casino, a haven where each game is a new adventure and every spin a potential story of victory. It’s not just the variety of games that makes All Slots Casino stand out, but the quality and the immersive experience they offer.

- A Spectrum of Games: From the adrenaline rush of modern video slots to the strategic depths of table games, there’s a game for every mood and moment.

- Engaging Features: With All Slots Casino 25 free spins on select games, players get the chance to explore and enjoy without extra cost.

- Constant Innovation: The casino regularly updates its game library, adding newer, more thrilling games to keep the excitement alive.

- Exclusive Bonuses: The allure is heightened with offers like All Slots Casino 25 free spins, a bonus that doubles the fun and potential winnings.

- Quality and Variety: The All Slots Casino games collection is not just vast but curated for quality, ensuring an unparalleled gaming experience.

- Player-Centric Approach: Feedback-driven updates ensure the gaming experience is always evolving, keeping pace with players’ preferences.

The variety and quality of All Slots Casino games are what set this platform apart. Whether you’re in the mood for a quick, flashy slots game or a more contemplative table game, All Slots Casino has you covered. All Slots Casino is not just a platform for gaming; it’s a gateway to a world where every game is a potential adventure, every spin a step towards a jackpot, and every player’s preference is valued and catered to. The All Slots Casino 25 free spins offer is more than just a bonus; it’s an invitation to explore new games and find new favorites without risk.

Easy Access and User-Friendly Experience

All Slots Casino stands out not only for its exciting games but also for its commitment to providing an easy and user-friendly gaming experience. This dedication is evident in every aspect of the casino, from the simplicity of getting started to the convenience of playing on any device.

- Hassle-Free Registration: Signing up is a breeze, allowing you to jump into the action quickly.

- Multi-Device Compatibility: Whether you’re on a desktop at home or using your mobile on the go, the All Slots Casino mobile login process is seamless and intuitive.

- User-Friendly Interface: Navigating the casino is straightforward, making it easy for both beginners and seasoned players to find their favorite games.

- Download and Instant Play Options: Players have the choice of downloading the casino software with the All Slots Casino download free option or playing directly through their browser.

- Regular Updates: The casino continually updates its platform, ensuring a smooth and glitch-free gaming experience.

- Easy Access to Support: Should you need assistance, the help center is just a few clicks away.

The All Slots Casino mobile login feature is a highlight, providing players the flexibility to play anytime, anywhere. This mobile-friendly approach means you’re never far from your favorite games, whether waiting for a bus or relaxing in a park. The All Slots Casino download free feature allows for a personalized gaming experience. Players who prefer a dedicated gaming environment can easily download the software, ensuring faster load times and a more stable connection.

All Slots Casino’s commitment to easy access and a user-friendly experience ensures that your focus remains on enjoying the games, not navigating complexities. With mobile, gaming on the go becomes a pleasure, while the All Slots Casino download free option caters to those who prefer a more traditional gaming experience. Here, your convenience and enjoyment are paramount.

Free Spins and Bonus Offers

At the heart of the All Slots Casino experience are the tantalizing free spins and bonus offers that transform ordinary gaming sessions into extraordinary adventures in fortune. These bonuses are designed not just to entice, but to enhance your gaming experience significantly.

- Welcome Bonuses: New players are greeted with open arms and generous offers, setting the tone for an exciting gaming journey.

- No Deposit Free Spins: The All Slots Casino free spins no deposit offer is a fan favorite, allowing players to try their luck without any initial investment.

- Ongoing Promotions: The excitement continues with regular promotions including more All Slots Casino free spins no deposit bonuses, keeping the thrill alive.

- Loyalty Rewards: Consistent play is rewarded, with players earning points that can be converted into additional gaming credits or bonuses.

- Seasonal Specials: Keep an eye out for seasonal offers, where players can snag additional free spins and bonuses.

- Exclusive Offers: The All Slots Casino 50 free spins promotion is an example of exclusive offers available to dedicated players, providing ample chances to hit the jackpot.

All Slots Casino’s Exciting Bonus Offers

Dive into the world of All Slots Casino, where excitement meets opportunity through an array of captivating bonuses and promotions. From no-deposit free spins to exclusive loyalty rewards, each offer is tailored to enhance your gaming journey. Below is a comprehensive table that breaks down these enticing offers, detailing the type of bonus, what it entails, any required codes or promotions, and the necessary criteria to qualify. Let’s explore the pathways to added fun and potential winnings at All Slots Casino.

| 🌟 Offer Type | 📜 Description | 🗝️ Code/Promotion | 📌 Requirements |

| 🎉 Welcome Bonus | Generous initial deposit bonus for new players. | No code needed | New registration |

| 🎰 No Deposit Free Spins | Free spins awarded upon signing up, no deposit required. | Sign-up bonus | New registration, no deposit |

| 🔁 Ongoing Free Spin Promotions | Regular free spin offers for existing players. | Varies per offer | Active player status |

| 💖 Loyalty Free Spins | Free spins rewarded for frequent play and points accumulation. | Loyalty program | Earned through loyalty points |

| 🎁 Seasonal Specials | Time-limited offers during holidays or special events. | Seasonal code | Available during specific times |

| 🚀 Exclusive 50 Free Spins Offer | Special promotion granting 50 free spins. | Exclusive promotion | Qualifying criteria specified |

This table represents a unique blend of offers available at All Slots Casino. The table is designed to provide clear and engaging information about the variety of free spins and bonus offers, making it easy for players to understand and choose the ones that best suit their gaming style.

The All Slots Casino free spins no deposit bonus is particularly enticing, offering a risk-free way to enjoy your favorite slots. It’s an opportunity to experience the thrill of real money gaming without the initial outlay, a perfect option for new players testing the waters. The All Slots Casino 50 free spins offer stands out as a testament to All Slots Casino’s commitment to their player’s enjoyment. It’s not just about attracting players; it’s about providing them with real value and opportunities to win.

The free spins and bonus offers at All Slots Casino are more than mere incentives; they are integral parts of the gaming experience. With offers like All Slots Casino 50 free spins, players get more than they expect, making every gaming session at All Slots Casino a potentially rewarding adventure.

Playing for Real Money

The excitement at All Slots Casino reaches its peak when playing for real money. This is where the thrill of gaming becomes tangible, where each spin or hand can lead to substantial winnings. Playing for real money adds an extra layer of excitement and engagement to the casino experience.

- Wide Range of Betting Options: Catering to players of all budgets, from casual gamers to high rollers.

- Fair and Secure Gameplay: Ensuring a safe environment where players can confidently wager All Slots Casino real money.

- Jackpot Opportunities: With real money play, you’re in for a chance to hit life-changing jackpots and big wins.

- Rewarding Bonuses: Players making real money deposits can enjoy additional perks like the All Slots Casino 25 free spins offer.

- VIP Treatment: Regular real money players can expect VIP treatment with exclusive bonuses and promotions.

- Instant Withdrawals: Winnings can be withdrawn quickly and securely, making the satisfaction of winning All Slots Casino real money even more gratifying.

Playing with mobile All Slots brings an authentic casino experience to your device. It’s not just about the potential winnings, but also the heightened sense of excitement and achievement when your strategies and luck pay off. The All Slots Casino 25 free spins offer adds to the allure of playing for real money. These spins provide additional chances to play and win without extra cost, enhancing the overall gaming experience. It’s a perfect blend of risk and reward, where the free spins offer a safety net of sorts, allowing you to explore and potentially win more.

The real-money gaming experience at All Slots Casino is unmatched. Whether it’s the thrill of betting All Slots Casino or the joy of being rewarded with All Slots Casino 25 free spins, the platform ensures that each moment spent playing is filled with excitement, anticipation, and the potential for big rewards.

International Appeal

All Slots Casino distinguishes itself with a global footprint, resonating with players from different corners of the world. Its international appeal is a testament to the platform’s adaptability, inclusivity, and understanding of various gaming cultures and preferences.

- Global Accessibility: Available to players from various countries, embodying a truly international gaming platform.

- Localized Gaming Experience: Tailored features and games that cater to specific regions, like the All Slots Online Casino Australia market.

- Multilingual Support: Offering support in multiple languages, ensuring players from different countries feel at home.

- Currency Flexibility: Accepts various currencies, making transactions easy and convenient for international players.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Games and promotions are often tailored to respect and reflect the cultural nuances of different regions.

- Global Community: Players can enjoy a diverse community, competing with or against gamers from all over the world.

The All Slots Online Casino Australia segment highlights the casino’s commitment to providing a tailored gaming experience to different regions. Australian players can enjoy games and promotions specifically designed to suit their preferences and style. The user-friendly website www.All Slots Casino.com offers a gateway to this diverse gaming universe. No matter where you are, the site is your one-stop hub for all gaming needs, from playing your favorite games to accessing customer support.

The international appeal of All Slots Casino, exemplified by its accessibility of www.All Slots Casino.com, is a significant factor in its global reputation. It’s not just a gaming platform; it’s a cultural crossroads where players from all over the world come together to share their love for gaming in a vibrant, inclusive environment.

Conclusion

It’s clear that this platform is not just an ordinary online casino; it’s a comprehensive gaming universe that caters to every kind of player. The combination of a vast game selection, user-friendly experience, enticing free spins, and real money play options, all contribute to its standing as a top-tier gaming destination.

- Comprehensive Platform: All Slots Casino encapsulates everything a gamer could ask for – variety, excitement, and the chance to win big.

- Ease of Access: The accessibility of www.All Slots Casino.com means you’re only ever a few clicks away from your next gaming adventure.

- Commitment to Players: Their dedication to providing a seamless and enjoyable gaming experience is evident in every aspect of the casino.

- Global Community: Being part of All Slots Casino means joining a worldwide community of enthusiastic and like-minded gamers.

- Reliable Support: For any inquiries or assistance, the All Slots Casino contact number is readily available, ensuring you’re supported every step of the way.

- Future Prospects: With continuous updates and improvements, All Slots Casino is poised to remain a leader in the online gaming industry.

Visiting www.All Slots Casino.com opens the door to a world where every game is an adventure waiting to happen. All Slots Casino stands out as a premier online gaming destination, offering an unmatched combination of games, bonuses, and player support. It’s a platform where gaming dreams can turn into reality, and where every visit brings a new opportunity for excitement and wins. The availability of the All Slots Casino contact number underscores the platform’s commitment to customer service and support. It ensures that help is always on hand, making your gaming experience as smooth and enjoyable as possible.